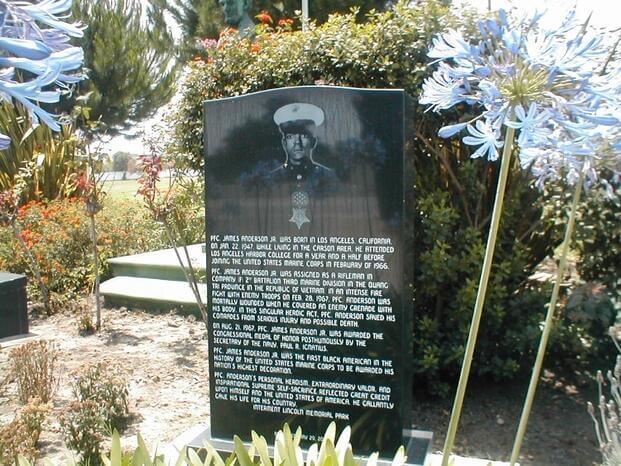

Every February, Black History Month shines a light on African Americans whose contributions and experiences shaped the nation. Some of those stories come from battlefields thousands of miles from home. One belongs to Pfc. James Anderson Jr., a 20-year-old Marine from Compton, California, who became the first Black Marine to receive the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Vietnam War.

Anderson was killed on Feb. 28, 1967, after throwing himself on an enemy grenade to shield the Marines around him during a vicious firefight in Quang Tri Province. He had been in Vietnam for less than three months.

A Kid From Compton

Anderson was born on Jan. 22, 1947, in Los Angeles. He grew up in nearby Compton, the first boy in a family that already included five daughters. He also had a younger brother, Jack. His parents, Aggiethine and James Anderson Sr., raised their children in a household rooted in faith.

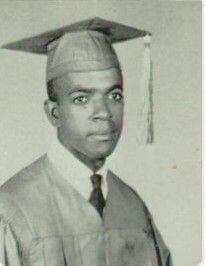

Those who knew Anderson described him as gentle, caring and deeply religious. He played clarinet in the band at Centennial High School and sang in the church choir. He graduated 10th in his class in 1964. His niece, Denise Johnson-Cross, told the Department of Defense in 2023 that Anderson took part in organizations like the Boys and Girls Clubs and was an excellent dancer.

His sister Mary later told the Los Angeles Times that Anderson’s future seemed clear.

“His whole life was centered on being a minister and working for the Lord,” she said. “That was his purpose.”

After high school, Anderson enrolled at Los Angeles Harbor Junior College to study pre-law. He spent a year and a half there before making a different choice.

With the Vietnam War escalating, Anderson enlisted in the Marine Corps on Feb. 17, 1966. Mary also mentioned that her brother once said he couldn’t kill anyone. Yet he signed up anyway.

Cross also recalled the decision decades later. “This was a choice that he made,” she said. “What strikes me now that I am a grandmother is that he was only 19.”

Before leaving for the Marine Corps, Anderson drove a 1965 Chevrolet Impala painted Evening Orchid, a rare color only offered for a single model year. He would let Cross sit behind the wheel while he washed and polished it.

Shortly after he shipped out for Vietnam, someone stole the car.

From San Diego to the DMZ

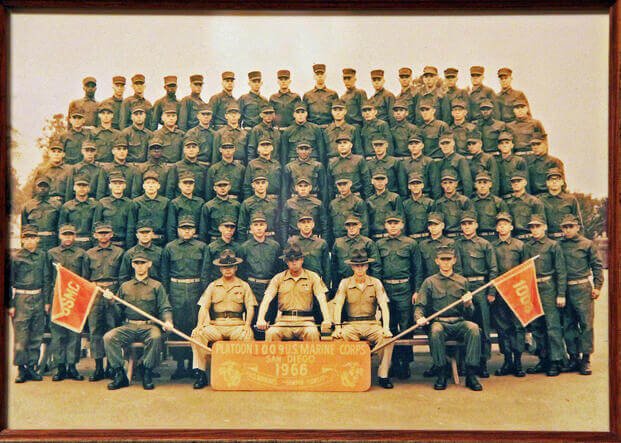

Anderson reported to the 1st Recruit Training Battalion at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego. He earned a promotion to private first class upon graduating boot camp in August of 1966. He then moved to Camp Pendleton for advanced infantry training.

By December 1966, Anderson was in the Republic of Vietnam. He was assigned as a rifleman with Company F, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines, 3rd Marine Division, operating in Quang Tri Province. The area sat just south of the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam. It was among the most dangerous areas to be stationed in the entire war.

The 3rd Marine Division had been battling elements of the North Vietnamese Army’s 324B Division in the region since the previous summer. Operation Prairie, a six-month campaign launched in August 1966, had cost 226 Marine lives while inflicting an estimated 1,700 enemy casualties.

When that operation ended on Jan. 31, 1967, Operation Prairie II picked up immediately. Its mission was the same. Find and destroy enemy forces infiltrating south across the DMZ.

Brig. Gen. Michael P. Ryan commanded the forward element of the 3rd Marine Division during Prairie II. He had three infantry battalions, two reconnaissance companies and supporting arms at his disposal. The early weeks of the operation were quiet. That changed sharply at the end of February.

Ambush Northwest of Cam Lo

On the morning of Feb. 27, 1967, a Marine reconnaissance patrol operating roughly five kilometers northwest of Cam Lo Combat Base stumbled into the enemy. The patrol tried to ambush two North Vietnamese soldiers. Those soldiers turned out to be the lead element of a company from the 812th Regiment, 324B Division. The enemy force quickly surrounded the recon Marines, who called for assistance.

Multiple Marine units, including elements of 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines, moved to help them before the fighting escalated. Anderson’s unit, Company F, was among them. On the morning of Feb. 28, the North Vietnamese launched a massive attack on Marine positions with over 150 mortar rounds and ground assaults from three directions

The company had pushed through dense jungle, trying to reach the besieged reconnaissance patrol. Anderson’s platoon led the advance. They made it roughly 200 meters before enemy small arms and automatic weapons fire tore into them.

The platoon scrambled to return fire in the thick vegetation. Anderson found himself on his stomach, packed shoulder to shoulder with fellow Marines barely 20 meters from the North Vietnamese positions. Several Marines had already been hit. The jungle was so dense the men could hardly move.

Then a grenade landed in the middle of the group. It rolled right alongside Anderson’s head.

There was no time to throw it back. Anderson reached out, grabbed the grenade and pulled it tight against his chest. He curled his body around it just before it detonated. The blast killed him instantly. Several nearby Marines caught shrapnel, but Anderson’s body absorbed the brunt of the explosion.

Many members of his platoon survived because of his actions. Anderson had just turned 20 a few weeks prior to his death.

Maj. William T. Macy delivered the news to Anderson’s parents.

“They took it well and bravely,” Macy said. “They’re that kind of family, proud and strong and grateful for having such a son.”

The First Black Marine Medal of Honor Recipient

On Aug. 21, 1968, Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius posthumously awarded Anderson the Medal of Honor at Marine Barracks Washington, D.C. His parents, James Sr. and Aggiethine, accepted the medal on behalf of their son.

The ceremony marked a significant moment in American military history. Anderson became the first Black Marine in history to receive the nation’s highest award for valor.

It was a key moment in Marine Corps history. Black men had not even been permitted to serve in the Marine Corps until 1942, when the first Black recruits trained at the segregated facility at Montford Point, North Carolina. Those that served in World War II and the Korean War were often mistreated, overlooked for awards and passed over for promotions.

Anderson was one of 23 African Americans who earned the Medal of Honor during the Vietnam War. He was also one of only six Black Marines to ever receive the decoration. Anderson earning the medal signaled that the Marine Corps, an institution with a long and complicated history on race, was evolving for the better.

Mary understood her brother’s sacrifice. He acted, she said, “because of his faith and his belief in mankind. He always cared about other people.”

Anderson was buried at Lincoln Memorial Park in Carson, California. His name is etched on Panel 15E, Row 112, of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

A Marine Corps Hero

In 1972, the Marine Corps dedicated Anderson Hall on Marine Corps Base Hawaii, home to his former unit. In 1983, the Navy acquired a Danish merchant vessel and renamed it USNS Pfc. James Anderson Jr.

The ship carried equipment to support a Marine expeditionary brigade from Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean until 2009. A memorial park in Carson and Anderson Avenue in Compton also bears his name.

In August 2024, the post office at 101 S. Willowbrook Ave. in Compton was formally renamed the Pfc. James Anderson Jr. Post Office Building after a bill introduced by Rep. Nanette Barragan was signed into law by President Joe Biden. Retired Sgt. Maj. Charles Cook Jr. attended the ceremony.

“A 20-year-old Black man felt the need to protect his platoon of 35-40 Marines and in that he gave his life,” Cook said. “That’s a Black man who had went through all kinds of stuff before he got there to do something bigger than him. That’s a Black veteran.”

The post office renaming held a special connection to the Anderson family’s past. After the Medal of Honor was awarded in 1968, hundreds of condolence letters from Americans of all races and backgrounds poured into Compton from across the country.

Many didn’t know the family’s address. They simply wrote to “the mother of the Medal of Honor recipient” and the letters were delivered. Cross said those letters likely passed through the very post office that now bears Anderson’s name.

Even 59 years later, Anderson’s sacrifice remains an inspiration for all Marines. His name is now on buildings, streets and memorials from Hawaii to Washington, D.C. The quiet kid from Compton who wanted to preach sermons ended up becoming the first Black Marine to earn the Medal of Honor by sacrificing his life to save others.